Use passphrases, not passwords

Anyone who creates online accounts will run into absurd variations of the above kinds of rules. Forced guidelines for passwords are well-meant – the goal is to get us to create safer passwords. But in practice the result can be the exact opposite: we create short passwords so we can more easily remember the complexity we are forced to slap onto it. That kind of password can meet the enforced requirements while at the same time being very weak.

So how does one create a strong password? To understand that it’s good to first understand a bit about how someone might go about trying to crack your password. Let’s take a quick look at three different methods, using them to note three simple guidelines for coming up with stronger passwords.

One approach is to guess specific, predetermined alternatives. There are lists available online of (millions of) the most commonly used passwords. At the top of these lists, year after year, you can find classics like 123456, password, and querty. (For more, see e.g. SplashData’s report on the most common passwords from 2015).

Passwords that are common enough to be on a list of common passwords are an excellent choice if your goal is to protect your accounts from infants and pets. If you want to protect yourself from others, read on.

So, number 1: avoid common passwords.

Another approach is to make guesses based on what one knows about the person in question. Either through personal contact with them or through information available on social media. This makes it possible to guess various combinations of names (family members, nicknames, pets), dates (birthdays or other significant dates), interests (hobbies, favourite movies), etc.

Number 2: avoid personal information in your passwords.

A third approach is what is called a brute-force attack. The way that works is that one, quite simply – but very time-consumingly (let’s pretend that’s a word) – guesses one’s way through every possible combination of characters. You cannot stop this kind of attack from eventually guessing your password, but by making your passwords long enough you can make it take a re(eeee)ally long time.

Number 3: use re(eeee)ally long passwords.

So, how does one come up with uncommon, impersonal, re(eeee)ally long passwords?

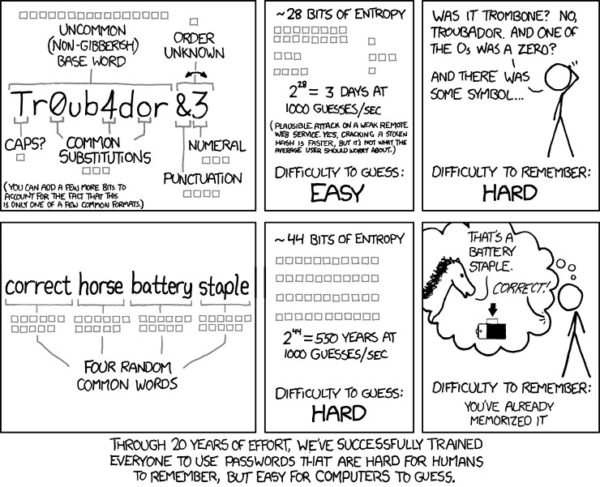

Luckily, coming up with strong passwords isn’t all that difficult. Like the brilliant webcomic xkcd has taught us, you can simply string a number of random words together into a password. (Four words is good, but computers will keep getting faster so more is more.)

“Password strength” by xkcd (www.xkcd.com)

Then, if you want (or have) to, you can throw in a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters and some bizarre symbols. Brute-force attacks can also be combined with other approaches, for instance trying combinations of existing words. So you could also either misspell some word or spell it phonetically.

(But, unfortunately, the people trying to get at our accounts know about our little tricks. Like swapping the letter “e” for the number 3, etc. So common substitutions are probably helpful, but not as helpful as we had hoped.)

The important thing to remember is that length is your key goal. That extra stuff is only if you can do it in addition to making it long, not instead of making it long. And if you’re worried you won’t remember even just a random set of words, then use a nonsensical or odd phrase instead.

Long and simple beats short and convoluted. “MadamMargaretMakesMadMunchies” beats “P@s5word#123.” And anything beats qwerty123. I’m begging you – ple(eeee)ase don’t use it!

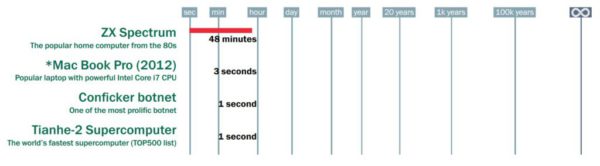

Brute-force attacks and you (or your password, at least)

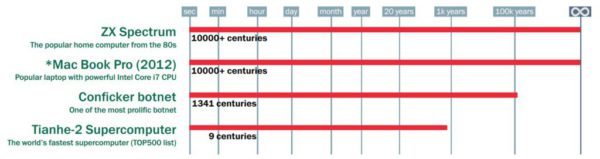

There are websites where you can get an estimate for the brute-force time of different passwords. For instance internet security company Kaspersky Labs has such a site. Their estimate for the brute-force survivability of the password qwerty123 makes the life-expectancy time of an extra in a zombie movie look rosy:

Brute-force times for various computers to crack the password “qwerty123” (source: Kaspersky Lab)

Based on what we’ve covered so far, let’s see if we can’t come up with a password that can outlast a snowflake in the Sahara. Again, random is better. But for this example we’re assuming we can’t be bothered to remember a completely random set of words. (Laziness: a feature, not a bug.)

I myself am part of the (probably rather large) section of humanity that does not both own a cat, and have given the cat (that I don’t own) the name Klaus. If we type in the password “IdonthaveacatcalledKlaus” in the brute-force estimator things start looking up. It is estimated to take centuries (or more) to guess our password.

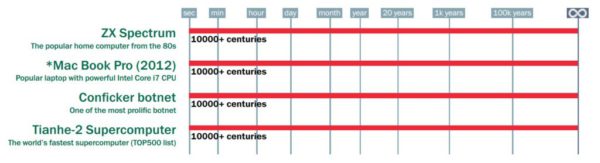

Brute-force times for “IdonthaveacatcalledKlaus”

If you speak another language in addition to English, it could be a good idea to use that for your password. The less common the language the better. (For instance, in writing this blog in Swedish I noticed that much shorter sentences were required to max out Kaspersky Lab’s estimated brute-force length in Swedish than in English.)

If you never bothered to learn another language (laziness: feature, not bug) then you can just go with password phrases that are as long as you can be bothered to type in. The previous example gave us centuries of time. That ought to do it. But let’s go a bit overboard on a final example to prove the point: My mom went to the moon and all I got was this lousy password.

Brute-force times for “MymomwenttothemoonandallIgotwasthislousypassword”

Not even the experts at Kaspersky Lab are willing to guesstimate how long brute-forcing this would take. But it doesn’t seem entirely unlikely that, in addition to all of our friends and relatives being long gone, by the time this is brute-forced the sun itself may well have started dying.

Not to trivialize the significance of our insightful social media updates, but if you notice that the sun has evolved into a red giant that has started engulfing nearby planets while frying away all the water from ours, then you arguably have bigger problems than someone having finally brute-forced their way into one of your accounts.

TL;DR

Forget passwords, use passphrases. Longer is better, more is more.