Data breach,Security,Shadow Brokers,Vulnerabilities

The NSA keeps vulnerabilities a secret – and the Shadow Brokers sell them

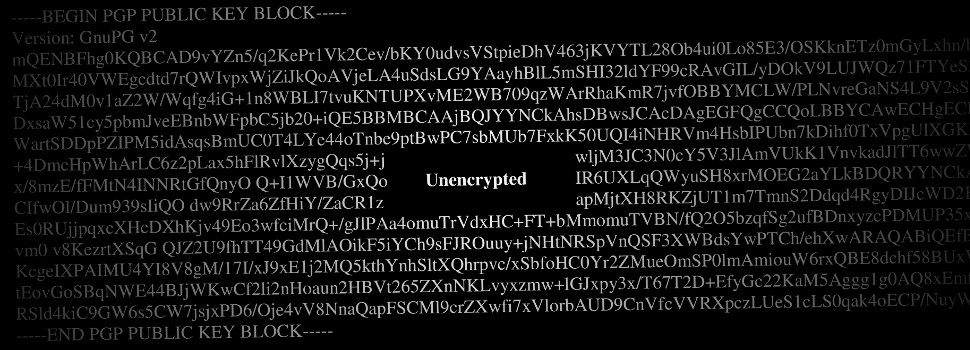

You can find all kinds of unusual things on the Internet. But last August something… unusually unusual popped up. A group calling themselves the Shadow Brokers announced that they would be auctioning off cyber weapons to the highest bidder.

What’s more – they claimed that these weapons were developed by the US.

The Shadow Brokers announce a cyber weapons auction. (Pic: Wayback Machine, web.archive.org)

A bit of background: white hat hackers, vulnerabilities, and “zero days”

Security researchers and so-called “white hat hackers” often work on trying to find vulnerabilities in computer programs. Previously unknown vulnerabilities are called “zero days.” If these researchers and white hat hackers find a zero day vulnerability in a program, they will inform the company who develops the program so that they can fix the vulnerability in question.

White hat hackers play a crucial role in society: they help secure our programs against their devious counterparts, the hackers who would exploit these vulnerabilities for personal gain (also called “black hat hackers”).

One would hope that governments would act like white hat hackers – that they would inform companies of new vulnerabilities they discover.

As it turns out, that isn’t always the case.

Hoarding – and exploiting – vulnerabilities (NSA style)

A huge case regarding a vulnerability discovered back in 2014 (Heartbleed) led to then-president Barack Obama making a statement regarding the United States’ standpoint on discovered vulnerabilities. The standpoint? The US would inform about all vulnerabilities it found. Except in cases where not doing so fulfilled “a clear national security or law enforcement need” (e.g. the New York Times).

That the US is keeping some zero days a secret isn’t in itself news. Back in 2010 the world learned about Stuxnet, a malware (a worm, to be more precise) believed to be the result of a joint effort by the US and Israel. Stuxnet utilized several zero days in targeting (and sabotaging) Iran’s nuclear program (nuclear centrifuges, to be more precise).

Keeping zero days a secret is far from unproblematic. As the Shadow Brokers case shows us, secrets can leak – e.g. through a data breach. Furthermore, companies aren’t likely to be thrilled when they find out their products have been vulnerable for years – due to a zero day their own government knew about but didn’t tell them existed. (As was the case with Cisco, see e.g. Ars Technica.)

New insights into US secrecy regarding vulnerabilities (both as a result of the Shadow Brokers leaks as well as another significant leak: Vault7) have led to discussions regarding this practice of secrecy (e.g. Motherboard and Greenberg in Wired). However, no changes to this policy have been announced. (And smart money is on not holding your breath.)

From the latest Shadow Brokers leak: Windows and SWIFT vulnerabilities

Since the Shadow Brokers first appeared last summer they have reappeared every now and again with new tools and vulnerabilities to sell or auction off. However, business hasn’t seemed to flourish, leading to a lot of stuff being released free of charge.

Among the latest batch was information about vulnerabilities in various versions of Windows as well as in the SWIFT payment system.

Microsoft Windows

The short version: the vulnerabilities Shadow Brokers released had, it turned out, been patched by Microsoft just the previous month. The story of how and when Microsoft patched some key vulnerabilities had some unusual twists and turns, leading to speculation regarding what Microsoft knew and how they knew it. (See e.g. Engadget for more.)

If you are an average home user and have recently updated your system, or your computer updates automatically, then you should be fine. If, for whatever reason, you haven’t updated your computer over the past month or so, then stop reading now and go do it! (I’ll wait.)

SWIFT

Another thing we learned from the latest Shadow Brokers outing was that vulnerabilities in the SWIFT network/payment system were among the secrets the NSA kept from the world. The US used to have the right to monitor SWIFT transactions, but that ended in 2013. Lee Mathews piece in Forbes offers some historical insight into the case of the NSA and SWIFT, and how the loss of the right to monitor SWIFT payments may have led to their interest in discovering vulnerabilities in SWIFT.

And then keeping them a secret.

(Well… trying to, at least.)