Internet of Things (IoT),Vulnerabilities

On Hypponen’s law: Be smart, not vulnerable

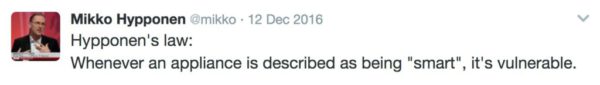

A while back I was scrolling through my Twitter feed when I came across an interesting tweet:

I have read plenty of laws, theories, and hypotheses during my time in academia, so I was well aware of the unwritten rule that they are supposed to take dozens of pages to explain, be unnecessarily and inexplicably convoluted, and remain completely divorced from any practical relevance. Clearly, Hyppönen was doing it wrong.

Or was he? I decided to see if I could get him to tell me the story behind his law. Here’s what I learned.

The Internet is on fire (and your washing machine isn’t doing too well, either)

During the early winter of 2014, Mikko Hyppönen was getting ready for a public appearance. He had been asked to speak at TEDx in Brussels in December and he wanted to make his speech an exceptional one. It was around this same time that the Internet of Things, or “IoT”, was becoming increasingly commonplace.

Seemingly nothing was too large or too small for manufacturers not to stick a computer into it and connect it to the Internet, thus becoming “smart”. Smart washing machines, smart TVs, smart watches – even smart light bulbs.

Hyppönen is Chief Research Officer at F-Secure, a Finnish Internet security and privacy company. So it’s understandable that he would look at new developments from a different perspective. While the rest of us were examining the new features of our smart appliances (“Honey, the washing machine called while you were out. Your boxer shorts are ready.”), Hyppönen was examining the security of these new appliances.

The results weren’t promising: any smart device you examined closely enough proved to have severe vulnerabilities. This point – that smart is vulnerable – made its first public appearance in his Brussels TEDx talk, titled The Internet is on fire. (Which is also the talk Hyppönen considers to be his best yet. You can find it on Youtube or Hyppönen’s website.)

Mikko Hyppönen (picture credit: TED)

Meh… How bad could it be?

Pretty bad, as it turns out. Some of the more impressive examples of Hyppönen’s law in action came during the fall and winter of 2016, in the form of the something called the Mirai botnet.

The term “botnet” is commonly used to refer to a collection of Internet-enabled computers that have come under the control of some third party (the Bad Guys). At first, our computer was ours alone to control. But then we clicked on a link we shouldn’t have, opened a file we shouldn’t have, or maybe we simply clicked on enable content (Hyppönen: “Never enable content”). And now, unbeknownst to us, our computer is sending out spam and wreaking digital havoc.

What made the Mirai botnet unique was that it consisted entirely of IoT devices. Malicious code had been programmed to surf the Internet, looking for IoT devices. When it found a device, it was programmed to try a predefined list of several dozen default usernames and passwords to gain entry into, and thus control of, the device. Anyone who had taken the time to change the default password of their IoT device was safe from this attack. But, as it turned out, not too many of us had done that.

Over a hundred thousand IoT devices were caught up in the botnet, combining forces to perform so-called distributed denial-of-service attacks. In brief, this kind of attack overwhelms a website by sending it so many requests from all the various bots around the world that the website breaks under the pressure and goes down. It’s the digital equivalent to sending so many people to a physical store that no-one else can get in.

The Mirai botnet’s targets ranged from an individual security journalist to multiple sites critical to much of the US Internet infrastructure. Our IoT devices were, albeit temporarily, bringing a significant chunk of the Internet to its knees.

The weakest link (Or, I know what your water boiler did last summer)

Some of us might not care about our IoT nicknacks moonlighting as evil minions as long as they leave us out of it. Unfortunately, there are plenty of ways in which IoT vulnerabilities can hit much closer to home. “An IoT device is often the weakest link in a network,” Hyppönen notes.

For example, IoT light bulbs have been used as gateways into a network, allowing attackers to circumvent traditional network security. IoT water boilers have been used to access WiFi passwords. Smart TVs and cars have been infected with ransomware – an increasingly popular kind of malware that encrypts your data and then demands a ransom in order to decrypt it.

But it wouldn’t have to stop at one device. As one example of a worst-case scenario, Hyppönen notes that an IoT vulnerability could lead to all of a user’s connected computers being infected with ransomware. And, at work, a vulnerable IoT device could put all connected computers and stored data at risk – without the company’s IT department even knowing the device is there.

Why is smart vulnerable?

A big reason why the situation is so bad, Hyppönen notes, is simply that we aren’t learning from our mistakes.

One of the things people learned ages ago about computers is that outdated systems are vulnerable. And one of the things people learned ages ago about, well… people, is that we as users aren’t very likely to go online to see if there are any important software updates available for our computers.

To address these issues, computers these days commonly offer automatic updates. But… IoT devices don’t. The software running your brand-spanking-new IoT appliance may well be dangerously outdated before you’ve even gotten it out of the box.

And, to make things worse, there’s also the issue of so many of us not taking the time to change our IoT device default passwords. Default passwords enabled the Mirai botnet, and have been a popular target of other attacks as well.

Another important lesson came with the dawn of the Internet revolution: convenient features like being able to use unencrypted communication to remotely log in to and control your computer from far away seem considerably less convenient once you realize that everyone else on the Internet also can remotely log in to and control your computer.

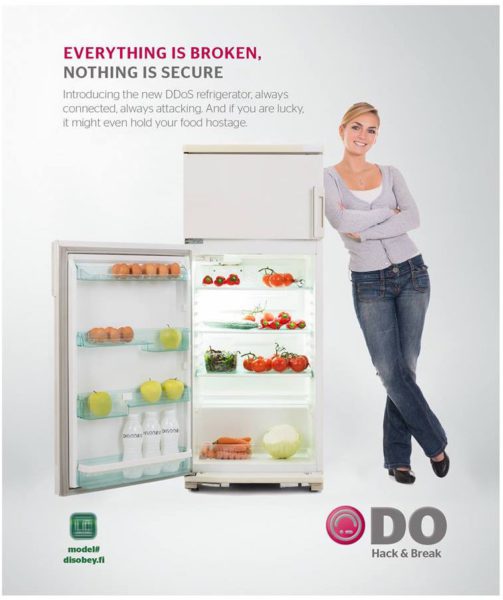

This vulnerability was due to insecurities inherent in a communications protocol called Telnet. Having Telnet enabled on any Internet-connected computer has, since the late 90s, been considered a Very Bad Idea. And who wants to take a guess at what communications protocol IoT devices commonly allow? (Hint: it starts with “Telne”.)

Spoof ad featuring vulnerable IoT fridge (picture credit: Disobey.fi)

I see vulnerable devices

The basic reason why it’s so hard to solve IoT vulnerabilities, Hyppönen notes, is that “when a consumer goes to the store to buy a new washing machine, security isn’t an important criteria.” Running down a list of criteria, he notes that price will come first. Maybe colour will also be on the list somewhere. And people might also ask how much laundry the machine can handle at a time. “But consumers don’t ask: Does this washing machine come with a firewall?”

Manufacturers, on the other hand, know that they are competing primarily on price. Since no one is asking about security, and since they can’t raise the price without losing in competitiveness, they aren’t going to invest in improving the security of their appliances.

But don’t despair. Well, at least not yet – because it gets worse.

Winter IoT is coming

As the hardware needed to connect an appliance to the Internet becomes cheaper, we will become surrounded by an increasing amount of new smart devices. And, for any reader who’s thinking, OK – then I just won’t buy any IoT appliances, Hyppönen has an unsettling reply: “Yes you will.” When it becomes cheap enough to add IoT features to a device, he continues, “manufacturers are going to do it – whether they tell you about it or not.”

These days, IoT features are generally designed to be useful to the user, but that won’t necessarily always be the case. You might not see the value in your toaster being connected to the Internet. But manufacturers will see value in getting data about their products. They may want to know how many units of a particular model are in use. Or how often they are used. Or they may want to know which countries or cities have how many of their products, so they know where to target their marketing.

Even if it’s just a toaster. Even if there’s no mention of it being hooked up to the Internet. When it becomes cheap enough to gather data, companies will want to do it. “The IoT revolution is coming,” Hyppönen proclaims, “Whether you like it or not.”

Make IoT smart again

After my talk with Hyppönen, I felt like ripping apart every appliance in my house just to make sure there weren’t any undocumented Internet-enabling bits or pieces anywhere. (Not that I would have been able to spot them anyway.) But, reassuringly, his take on the future of IoT isn’t quite so gloomy.

“I hope that, ten years from now, we will be able to look back on an IoT revolution that was reminiscent of the Internet revolution: it brought some bad stuff, sure. But overall it gave us more good than bad.”

A large part of the responsibility for making that happen seems to lie with us, the consumers. As more and more stuff gets connected to the Internet, we need to let manufacturers know that we care about IoT security. Ask not Do you have any IoT doorbells; ask Do you have any firewalled, automatically updated, Telnet-disabled doorbells.

And let’s hope, ten years from now, “smart but vulnerable” will be how we describe our favourite movie protagonist, not our toaster.